It’s time to take a closer look at the iconic inaugural address delivered by U.S. President John F. Kennedy in 1961. His life and tragic death have become the subject of countless books, films, and conspiracy theories — but what stands behind the image of this legendary political figure?

You’ve probably heard his most quoted line:

“Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.”

This powerful call to service became one of the most memorable moments of Kennedy’s presidency and a defining quote in American political rhetoric.

In this article, you’ll explore key moments in John F. Kennedy’s life, discover interesting facts surrounding his inaugural speech, and dive into a detailed rhetorical analysis and summary of one of the most influential speeches in U.S. history.

John F. Kennedy: A Brief Biography of the 35th U.S. President

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th President of the United States, remains one of the most iconic political and public figures in American history.

He was born in 1917 in Brookline, Massachusetts. His father, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, was a wealthy businessman and political insider who, thanks to his friendship with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, secured several government appointments.

Joseph Kennedy placed great importance on education and sent his sons to the prestigious Choate Boarding School in Connecticut. Teachers described John as intelligent and insightful, though not a particularly diligent student. He often lacked motivation if a subject didn’t interest him. However, he was deeply drawn to literature and poetry — especially the works of Robert Frost, who would later recite at his son’s presidential inauguration.

In 1937, Joseph Kennedy was appointed U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain. While studying at Harvard University, John remained an average student until he visited his father in London. Witnessing the growing tension in pre-war Europe left a deep impression on him. This experience marked a turning point in his life.

Inspired by international affairs and the importance of leadership, Kennedy returned to Harvard with a new sense of purpose. He became involved in campus life, joined the Hasty Pudding Club and the elite Spee Club, and contributed to the university newspaper.

After graduating in 1940, Kennedy joined the U.S. Navy, serving in the Office of Naval Intelligence. During World War II, he commanded a fast patrol torpedo boat (PT-109) in the South Pacific. For his heroism during the events of August 1–2, 1943, he received several military honors, including the Purple Heart, the Navy Cross, and the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

In 1944, tragedy struck the Kennedy family when John’s older brother, Joe Jr., was killed in combat. With Joe gone, the family’s hopes shifted to John. After the war, he decided to enter politics.

In 1946, at just 29 years old, Kennedy was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives by the people of Massachusetts — launching his political career. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1952, and just eight years later, in 1960, at the age of 43, John F. Kennedy was elected President of the United States.

John F. Kennedy’s Presidency: Challenges, Reforms, and Tragedy

John F. Kennedy wasn’t just the youngest elected president in U.S. history — he was also the first Catholic to hold the office. His rapid rise sparked both admiration and suspicion: some envied his charisma and success, while others doubted his ability to lead due to his youth and religious background.

Perhaps that’s why Kennedy felt a constant need to prove his strength — especially on the global stage. His presidency unfolded during one of the most tense periods of the Cold War, when the United States faced growing pressure from the Soviet Union and the spread of communism.

Foreign Policy Under Pressure

Kennedy’s time in office was marked by major foreign policy crises. He inherited the escalating Vietnam War and gave the green light to the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion — a failed U.S.-backed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba.

But the greatest international test came in October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis. For thirteen days, the world stood on the brink of nuclear war, as the U.S. and USSR faced off over Soviet missiles deployed in Cuba. Kennedy’s careful diplomacy, including secret back-channel negotiations, ultimately averted catastrophe. His handling of the crisis is often viewed as one of his most significant achievements.

Civil Rights and Domestic Struggles

Kennedy also faced growing unrest at home. In the southern states, racial discrimination and violence against African Americans were escalating, as calls for civil rights became louder. Initially hesitant to act, Kennedy eventually took a stronger stance.

In 1963, he delivered a televised address titled Report to the American People on Civil Rights, outlining his commitment to equal access to education, public facilities, and voting rights. His proposals laid the foundation for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — a landmark law that:

- Banned segregation in schools and public spaces

- Prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin

- Outlawed unequal voter registration requirements

- Aimed to end employment discrimination

This act remains, in the words of historians, “one of the most significant legislative achievements in American history.”

A Presidency Cut Short

Tragically, John F. Kennedy did not live to see the Civil Rights Act passed into law. On November 22, 1963, while riding in a motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, Kennedy was shot and killed by Lee Harvey Oswald. The assassination shocked the nation and the world, ending a presidency full of promise and potential.

Behind the Words: How John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address Was Created

John F. Kennedy wasn’t born a great orator — his rhetorical power came from years of disciplined effort and constant refinement. His now-legendary inaugural address, delivered on January 20, 1961, was the result of meticulous preparation and collaboration, but also deeply personal input.

Although Kennedy worked closely with his trusted advisor and speechwriter Ted Sorensen, he was far from a passive recipient of someone else’s words. In fact, historical archives show that Kennedy personally revised every draft, making handwritten notes, corrections, and edits. His commitment to shaping the speech himself reflects how seriously he viewed the power of words.

To craft a message that would resonate with the American people and the world, Kennedy and Sorensen studied some of the greatest speeches in history. Kennedy asked Sorensen to read and draw inspiration from Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, as well as all previous U.S. presidential inaugural speeches. He even sought feedback from religious leaders and colleagues, determined to create a speech that would stand the test of time.

During the actual delivery of the address, Kennedy made 32 spontaneous changes, deviating from the prepared text just as Martin Luther King Jr. would famously do in his speeches. One of those unscripted edits gave rise to the most iconic line of the speech:

“Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.”

This now-immortal quote was inspired by the motto of Choate School, where Kennedy studied as a teenager:

“Ask not what your school can do for you — but what you can do for your school.”

The inaugural address was a resounding success. Following its delivery, John F. Kennedy’s approval rating soared to 75%, reflecting the speech’s emotional impact, clarity of vision, and call to national service.

Fascinating Facts About John F. Kennedy’s Inauguration

John F. Kennedy’s inauguration on January 20, 1961, wasn’t just a political event — it became a cultural and historical milestone filled with symbolism, innovation, and poetry. Here are some compelling facts about that day:

The Shortest Inaugural Address in U.S. History

Kennedy’s speech contained just 1,366 words, making it the shortest presidential inaugural address in American history — yet also one of the most powerful. Its conciseness gave it clarity and impact, every word carefully chosen.

The First Color Broadcast of a Presidential Inauguration

For the first time in history, a U.S. presidential inauguration was broadcast in color television. An estimated 60 million viewers watched Kennedy deliver his address — a record-breaking number for that era.

Robert Frost and the Power of Poetry

Kennedy’s love for literature played a unique role in the ceremony. For the first time ever, a poet was invited to participate in a presidential inauguration. The renowned Robert Frost, one of Kennedy’s favorite writers, recited his poem “The Gift Outright” from memory, as the glare of the sun made it impossible to read from his paper.

Here’s an excerpt from the poem Frost recited:

The land was ours before we were the land’s

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people…

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living…

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright…

To the land vaguely realizing westward…

Such as she was, such as she will become.

The presence of poetry at the inauguration — and Kennedy’s deep appreciation for the arts — helped elevate his inaugural speech into something greater than politics: a message of shared purpose, renewal, and inspiration.

His literary sensibility, shaped by years of reading and admiration for writers like Frost, helped him craft a speech that has endured across generations.

Rhetorical Analysis of JFK’s Inaugural Speech: The Rhythm and Flow of Language

One of the most striking features of John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address is its carefully constructed rhythm. Kennedy masterfully alternates long, complex sentences with short, punchy statements, keeping the audience engaged and emotionally attuned.

This dynamic use of sentence length prevents monotony and adds a natural musicality to the speech — it flows like poetry, not a political lecture. The variation in rhythm holds listeners’ attention and reinforces key messages.

Let’s take a look at one powerful example from the speech:

“Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage, and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world.”

This sentence is long, layered, and cumulative — unfolding gradually like a nesting doll, each phrase building upon the last to create a sweeping vision of generational responsibility.

Then comes the contrast — a sharp, emphatic declaration:

“Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty. This much we pledge—and more.”

The final phrase — “This much we pledge—and more” — is a short, deliberate sentence that anchors the paragraph and emphasizes commitment with clarity and strength. This deliberate shift from complexity to simplicity is what makes the speech so memorable and emotionally resonant.

Kennedy’s sense of rhythm wasn’t accidental — it was a rhetorical strategy designed to inspire, persuade, and move.

The Tone of JFK’s Inaugural Address: Clear, Direct, and Unifying

One of the defining qualities of John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address is its simplicity. The speech is free of complex terminology or academic jargon. Instead, Kennedy used clear, direct language — words that every American could understand.

And that was no accident.

Kennedy wasn’t speaking to politicians or scholars. He was speaking to the people — to farmers and teachers, factory workers and students, young and old alike. His goal was to unite the nation, to reassure and guide, and most importantly, to inspire faith and hope during uncertain times.

That’s why he avoided technical vocabulary. There was no need for abstract theories or difficult expressions. Every word in the speech was carefully chosen for its clarity, emotional weight, and accessibility.

The tone is confident but not arrogant, uplifting but not overly grand. It reflects Kennedy’s belief in shared responsibility and the power of collective action — and it does so in a language that speaks not only to the mind, but to the heart.

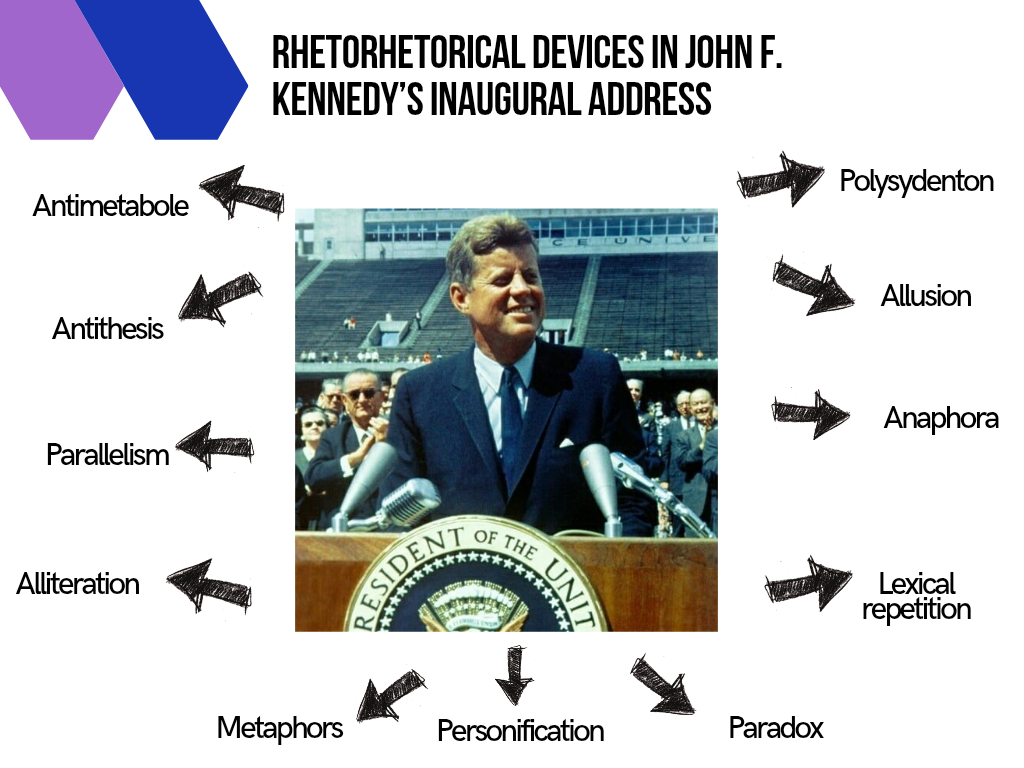

Rhetorical Devices in John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address: Figures of Speech and Tropes

John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address masterfully employs two main rhetorical figures — antithesis and parallelism — which are tightly intertwined throughout the speech. These core devices are enriched by other figures of speech and literary tropes that add depth and color to his message.

- Antithesis

Antithesis highlights contrasts between words, ideas, or images that share a connection, emphasizing difference through opposition. Kennedy’s most famous example is:

“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

Other examples include:

“Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.”

“We observe today not a victory of party but a celebration of freedom…”

“Not because the communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right.”

“Not as a call to bear arms… not as a call to battle… but a call to bear the burden…”

- Parallelism

Parallelism is the repetition of similar grammatical structures or patterns:

“United there is little we cannot do in a host of cooperative ventures. Divided there is little we can do…”

- Alliteration

The repetition of consonant sounds in nearby words creates rhythm and emphasis:

“Let us go forth to lead the land we love…”

“Pay any price, bear any burden…”

- Metaphor

Metaphors convey figurative meaning through comparison, enriching the imagery and engaging imagination:

“And if a beachhead of cooperation may push back the jungle of suspicion…”

“The bonds of mass misery”

“The chains of poverty”

- Personification

Attributing human qualities to inanimate objects or abstract ideas:

“To our sister republics south of our border…”

“But this peaceful revolution of hope cannot become the prey of hostile powers.”

“The dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity…”

- Paradox

A statement that seems contradictory but reveals a deeper truth:

“Only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed.”

- Lexical Repetition

Deliberate repetition of words or phrases for emphasis:

“…not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need; not as a call to battle, though embattled we are…”

- Anaphora

Repetition of initial words or phrases to create rhythm and reinforce ideas:

“Let both sides explore what problems unite us instead of belaboring those problems which divide us. Let both sides, for the first time, formulate serious and precise proposals… Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors.”

- Allusion

A reference to well-known historical events or speeches. Kennedy’s speech draws inspiration from Abraham Lincoln, for example:

“To that world assembly of sovereign states, the United Nations, our last best hope in an age where the instruments of war have far outpaced the instruments of peace.”

- Antimetabole

Repeating words in reverse order for emphasis and contrast:

“Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.”

- Polysyndeton

The repeated use of conjunctions to emphasize continuity or abundance:

“Formulate serious and precise proposals for the inspection and control of arms, and bring the absolute power to destroy other nations…”

Summary and Main Points of John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address

In the opening of his inaugural address, John F. Kennedy paints a vivid picture of a changed world — one where humanity holds immense power:

“The world is very different now, for man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe — the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God.”

Kennedy addresses not only allied and friendly nations, but also those he diplomatically refers to as “adversaries.” His tone is both subtle and politically sensitive, offering enemies a chance to change course:

“Finally, to those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace.”

In the second part of the speech, Kennedy calls for global unity and cooperation to build a better future together. He proposes ambitious steps toward progress:

“Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce. Let both sides unite to heed in all corners of the earth the command of Isaiah to ‘undo the heavy burdens… and let the oppressed go free.’ And if a beachhead of cooperation may push back the jungle of suspicion, let both sides join in creating a new endeavor, not a new balance of power, but a new world of law, where the strong are just and the weak secure and the peace preserved.”

This summary captures the essence of Kennedy’s vision — a world defined by hope, peace, and shared responsibility.